Projections by officials in the justice sector in New Zealand describing how quickly they believe the prison population will rise have consistently underestimated actual growth. In 2014, when the muster was about 9,000, officials forecast that figure would not rise to 10,000 in the foreseeable future. A year later, they predicted it might reach 10,000 in 2022. In fact, it hit 10,000 in December 2016,  six years earlier than predicted. In February 2018, it reached 10,695.

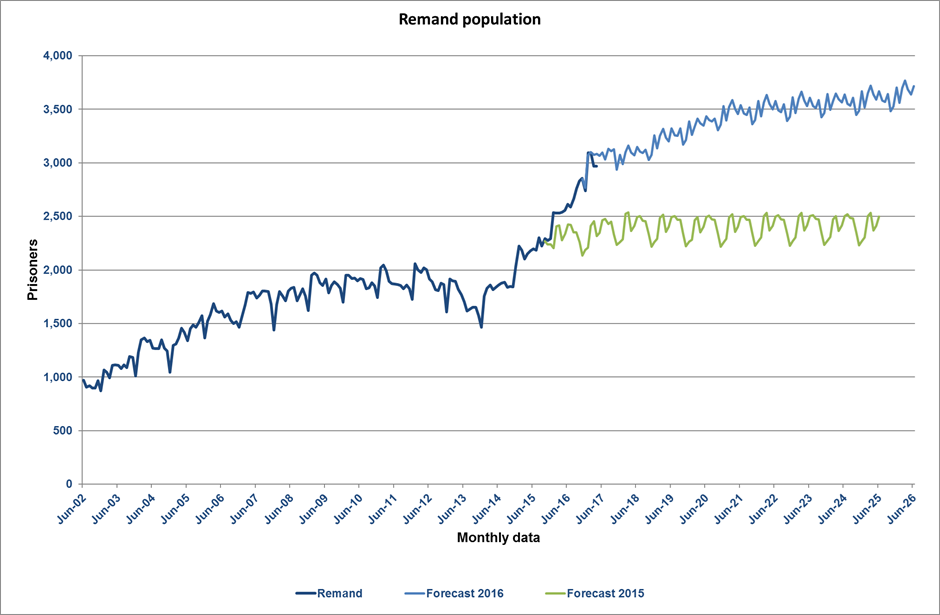

Chart showing the dramatic increase in remand population above justice sector forecasts after the Bail Amendment Act was introduced in 2013.

The two main legislative factors driving the growth in prison numbers.

1) Longer sentences: There has been a steady growth in the number of offenders receiving longer and longer prison sentences. This is due to a succession of ‘tough on crime’ legislative changes over the last 30 years. At the same time the Parole Board has toughened up making most prisoners serve at least 75% of their sentence. These days its pretty hard to get out early.

2) More prisoners on remand: Another legislative change, the Bail Amendment Act in 2013, led to a dramatic increase in the number of offenders held on remand. Justice sector projections indicated this Act would only add another 50 to 60 people to the prison population. Within three years, there were another 1,500 Kiwis on remand.

The reality is that the muster has been rising so much faster than Justice Sector projections, we now have a crisis. Stuff crime reporter, Matt Stewart says:Â “Prisons under ‘immense pressure’ with only enough space for 300 more inmates.”

In other words, the number of people incarcerated is rapidly outstripping capacity and it appears we need yet another prison. According to Justice Minister, Andrew Little, unless we start doing things differently, New Zealand will need to build a new one every two or three years. Â

Some quick fix solutions to this problem are described here. These will give the Government six years of breathing space to develop and implement more effective long term strategies.

Why are justice sector projections so inaccurate?

The problem is that policy advisors in the Ministry of Justice tend to operate in a silo. When considering the likely impact of a particular change in legislation, they generally fail to consult outside the Ministry: they don’t talk to police to find out how the police are likely to respond; and they don’t consult with judges or the Parole Board to get their views on the potential impact of a new law. Because the MOJ doesn’t consult widely enough, the officials making these projections rely on little more than guesswork and informed assumptions. Given this lack of consultation, it should be no surprise that their projections are consistency off the mark.

The problem is that policy advisors in the Ministry of Justice tend to operate in a silo. When considering the likely impact of a particular change in legislation, they generally fail to consult outside the Ministry: they don’t talk to police to find out how the police are likely to respond; and they don’t consult with judges or the Parole Board to get their views on the potential impact of a new law. Because the MOJ doesn’t consult widely enough, the officials making these projections rely on little more than guesswork and informed assumptions. Given this lack of consultation, it should be no surprise that their projections are consistency off the mark.