New Zealand’s prison population is out of control

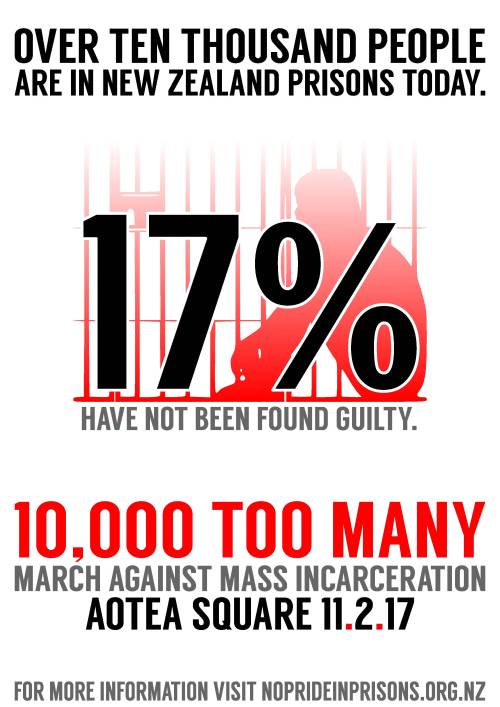

According to the World Prison Brief, in September 2017, New Zealand’s prison population hit an all-time high of 10,470 of whom 2,983 or 28.5% were on remand. This means we lock up 217 Kiwis per 100,000 of our population.

Our high rate of imprisonment puts New Zealand on a par with countries which have some of the most undemocratic and corrupt justice systems in the world. In fact, New Zealand now has a higher rate of imprisonment than 160 other countries. Click here for a list of war-torn countries we really don’t want to compare ourselves with.

New Zealand now has a higher rate of imprisonment than 160 other countries.

That includes democracies with which we have a lot in common. In England and Wales the rate of imprisonment is only 143. In Scotland its 135. In Australia, 167. In Canada it’s 114. Click here for a list of democracies that have lower rates of imprisonment than New Zealand.

Our crime rate is similar to these western democracies, but for some reason we lock up a lot more people (per capita). For a civilised, economically developed, (largely) corruption free country like New Zealand, this is a disgrace – or a ‘moral and fiscal failure’ to quote Bill English.

According to Kim Workman, New Zealand’s…

“problems with prisons started in 1987 with the infamous Law and Order general election, characterised by the get-tough messages, punitive bidding wars, and promises to the public to increase police numbers (now a triennial event)”.

At that time, New Zealand had less than 3,000 people in prison. There are now over 10,000.

Given the impact of penal populism in New Zealand over the last 30 years, proposals to cut the prison population may arouse a degree of fear mongering. It’s not just the so-called Sensible Sentencing Trust which is concerned about the ‘safety’ of the community; so is the Parole Board which has become increasingly risk averse. Most politicians, fearful of falling out of step with public opinion, are also worried.

Part of the problem is that the media are primarily interested in ratings and profit. New Zealand no longer has public service television and the mainstream media like to highlight stories about crime, especially violent crime. Because of all this attention, a majority of people in New Zealand mistakenly believe that crime is on the rise when, in fact, it has been on the decline for years. Criminologists refer to this process as ‘moral panic’, one of the factors driving penal populism.

Part of the problem is that the media are primarily interested in ratings and profit. New Zealand no longer has public service television and the mainstream media like to highlight stories about crime, especially violent crime. Because of all this attention, a majority of people in New Zealand mistakenly believe that crime is on the rise when, in fact, it has been on the decline for years. Criminologists refer to this process as ‘moral panic’, one of the factors driving penal populism.

“The media tends to highlight stories about crime, especially violent crime.”

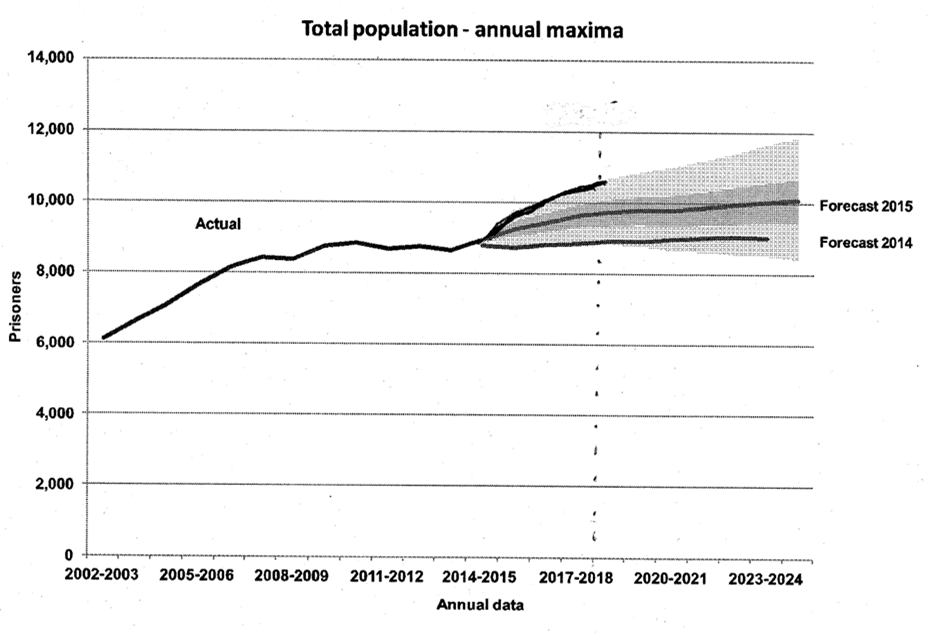

Justice Sector projections of the prison population

When new legislation is passed, the outcome of each change is always uncertain. It is hard to know how many extra people police may now prosecute; how judges will sentence those found guilty under the new law; or how the Parole Board will respond.

Justice sector projections depicting how quickly the prison population will rise have consistently underestimated actual growth. In 2014, when the muster was about 9,000, officials forecast that figure would not rise to 10,000 in the foreseeable future. A year later, they predicted it might reach 10,000 in 2022. In fact, it hit 10,000 in December 2016, six years earlier than predicted (see actual growth line in graph below).

The muster hit 10,000 in December 2016, six years earlier than predicted.

The reality is that the prison muster is rising faster than Justice Sector projections, to the point that we now have a crisis. The number of people being incarcerated is rapidly outstripping capacity and it appears we need yet another prison. According to Justice Minister, Andrew Little, unless we start doing something differently, New Zealand will need to build a new one every two or three years.

Justice sector projections have consistently underestimated the growth in prison numbers.Â

How safe are we?

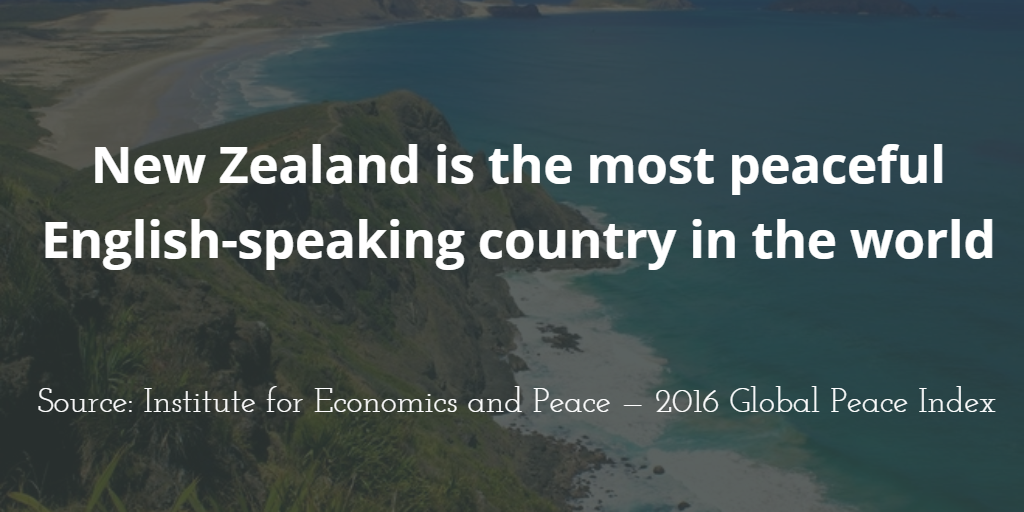

Despite all the fear mongering by the media, New Zealanders are much safer than we realise. In 2016, New Zealand was ranked the fourth safest country in the world on the Global Peace Index. In 2017, we were ranked second in the world – but ranked first among English speaking countries.

Despite all the fear mongering by the media, New Zealanders are much safer than we realise. In 2016, New Zealand was ranked the fourth safest country in the world on the Global Peace Index. In 2017, we were ranked second in the world – but ranked first among English speaking countries.

So compared with the rest of the world, New Zealand, is one of the two safest places to live, second only to Iceland whose rate of imprisonment is only 38 per 100,000.  But you wouldn’t think so if the main stream media in New Zealand is your primary source of ‘news’.

In 2017, New Zealand was ranked the second safest country in the world.

Another reality is that most people in our prisons are not vicious criminals. In fact, over half of all prisoners are classified by Corrections as either low or low-medium risk. Because of systemic flaws in the way Corrections assesses risk, some prisoners classified as ‘high risk’, should actually be reclassified as medium risk. A review of New Zealand’s rehabilitation and reintegration services by Canadian and US criminologists in 2012 found that:

“If guidelines from other correctional systems are prescient it would be reasonable to hypothesize that up to 30% of the offenders currently assessed as high risk in New Zealand prisons belong in lower risk bandsâ€.

So, could we let a few people out of prison? Or put less people in? New Zealand’s leading authority on this subject, Kim Workman, believes we could cut prison numbers by as much as 75%. At the 2017 election, Gareth Morgan’s Opportunities Party proposed reducing the muster by 40% over ten years. The Labour coalition is proposing to reduce it by 30% over 15 years.

However, both Kelvin Davis, the new Corrections Minister, and Andrew Little have been very vague about how they intend to achieve this. Both also seemed to think it was complicated and would take a long time. In public statements, both Ministers seem to think that cross-party agreement is required and have suggested only long term, slow and uncertain solutions.

This website suggests three quick fix strategies which would lower the prison population by between 3,000 and 4,000 and explains why this needs to be done within the next six years.