THERE are quick-fix solutions to the current crisis in prison capacity (the prospect of not enough prison beds to meet demand).Â

Some straight forward legislative changes will result in less prisoners held on remand (pending trial and sentencing), and more low-risk prisoners released earlier.

Our suggestions as to how this could be done are below – although ‘there is usually more than one way to skin a cat’. The important thing is that the Government investigates these or other short-term solutions to the crisis before trying to implement any long term solutions. Â

Â

Suggested Quick Fix Strategies

The Labour-led Government has set itself a goal to reduce the prison population by 30% in 15 years. Long term solutions, especially if they take 15 years to kick in, will not avoid the need for increased capacity in the immediate future.

Given that the Government has indicated it doesn’t want to build a new prison, and that Corrections is facing a crisis in capacity, decisive action is required to cut the muster now – in the next six months.  This campaign proposes four strategies which will make an immediate difference.

1) Reverse the effects of the Bail Amendment Act 2013 to cut the number of prisoners on remand

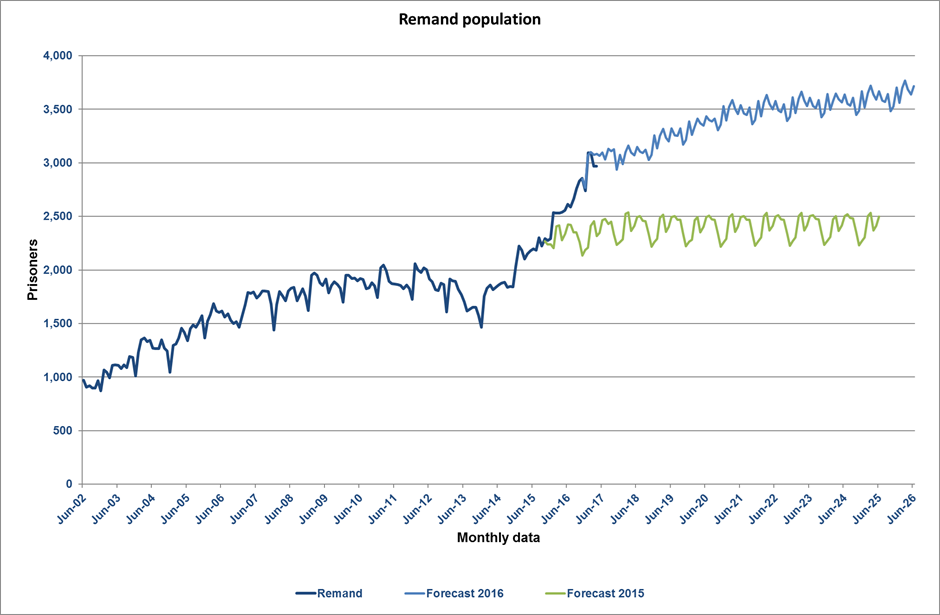

Of all the punitive legislation passed since 1985, the Bail Amendment Act of 2013 has produced the quickest and biggest bump in the muster by nearly doubling the number of prisoners on remand. The chart below shows that on a given day in 2017, there were 2,811 remand prisoners. But over the course of a year, a total of 11,500 people are remanded in prison, most of whom have yet to be convicted of a crime. Many are remanded simply because they have nowhere to live.

Chart showing the dramatic increase in remand population above justice sector forecasts after the Bail Amendment Act was introduced in 2013.

The Bail Amendment Act was introduced following the media frenzy manufactured by Garth McVicar after the murder of Christie Marceau in November 2011. Marceau was killed by 18 year old Akshay Chand. Prior to the murder, Chand had been arrested for kidnapping and threatening Marceau with a knife. Despite opposition from the police, he was bailed to an address not far from the Marceau family home and killed Christie 33 days later.

This was not a failure of the existing bail laws. The coroner’s report into Christie’s death, released on 6 March 2018, found that Judge McNaughton’s decision to release Chand on bail was the result of administrative failures in the justice system and the mental health system. It had nothing to do with existing Bail laws.

Chand was subsequently diagnosed with schizophrenia and found unfit to stand trial. The Judge was never made fully aware of the risk that he posed: a forensic health nurse in court advised the judge that Chand had been taking anti-depressant medication for two weeks and could be “safely and successfully” treated in the community. When granting bail, the judge naturally trusted the mental health professionals who assessed Chand prior to his court appearance rather than the police.

“This was not a failure of the existing bail laws. It was the result of a misdiagnosis and woefully inadequate risk assessment by the mental health services.”

After the murder, Garth McVicar took advantage of the Marceau family’s grief and persuaded her parents to start a campaign to have the bail laws amended. The media actively supported the campaign.

Sucked in by the Sensible Sentencing Trust, National passed the Bail Amendment Act. As a result, we now have another 1,500 people on remand. They’re being held in prison because a mental health nurse, not a judge, got it wrong and because National gave in to the relentless pressure from Garth McVicar and the media.  (Rather than change the bail laws there should have been an inquiry into the quality of forensic mental health services. Hopefully this will be part of the inquiry into mental health announced by Prime Minister, Jacinda Ardern in January 2018.)

Three years later, the Corrections Department mistakenly assumes we need a new prison.  We don’t. We just need to reverse the effects of the Bail Amendment Act on the Bail Act 2000. In the process we need to break this chain of erroneous assumptions driven by Garth McVicar, the media and knee-jerk political reactions.

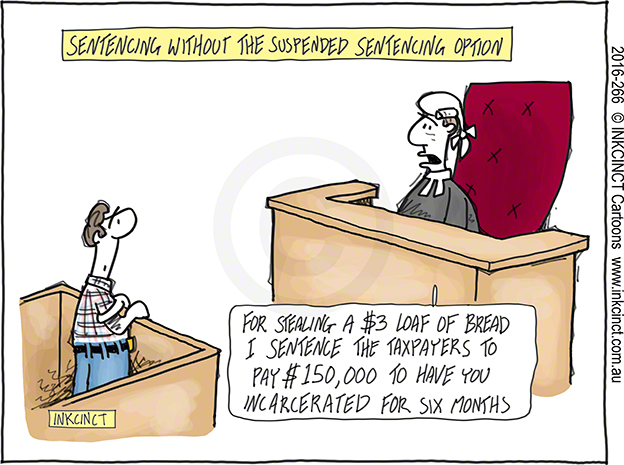

2) Eliminate very short sentences of six months or less

The Parole Act defines a short-term sentence as one of two years or less. In the scheme of things, these are actually very short sentences; thousands of offenders are sent to prison each year with very short sentences – often for just a few weeks or months. The turnover is very rapid because prisoners on short terms never serve their whole sentence; they’re automatically released after serving only half.

“42% of inmates are in prison for quite minor crimes”

This means short-termers are not required to appear before the Parole Board. With thousands of people on short term sentences cycling through our prisons every year, the Board would be totally overwhelmed if it had to make decisions about every single prisoner – 42% of whom are in prison for quite minor crimes. The release of those on short terms at the half-way mark is an administrative strategy which makes space in the prison system for more serious offenders on long term sentences – who do have to appear before the Board.

The prison population could be cut significantly if short term sentences of six months or less were restricted or abolished altogether.

There is little to be gained by sending people to prison on very short sentences. Incarceration does not work as a deterrent (see question 7 under Q&A) for most offenders and short termers are generally not able to access rehabilitation programmes in prison; these are generally reserved for more serious criminals on long sentences. What this means is that the prison population could be cut significantly if short term sentences of six months or less (actually 12 months or less due to half time release) were restricted or abolished altogether. This strategy was adopted in Germany to reduce its prison population.

3) Impose suspended sentences on offenders facing six to 12 months

Offenders serving sentences between six months and twelve months (effectively between one year and two years) could be given conditional or suspended sentences. Offenders with conditional sentences are only sent to prison if they re-offend during a given period of time – usually the length of the sentence. This was one of the strategies adopted in Finland where they cut their prison population by 78%.Â

Short-term prisoners make up 19% of the total prison population – that 1,900 inmates

Because they’re in and out quite quickly, in 2015, (very) short-termers made up only 19% of the total prison population on a given day. Out of 10,000 people in prison, that’s 1,900 inmates, most of whom would probably be assessed at low risk of reoffending. If we abolished short sentences of six months or less, and imposed suspended sentences on the remainder of those on short sentences (serving up to 12 months), most of the 1,900, perhaps 1,500, would no longer be in prison.

Add this to the 1,500 no longer held on remand and the prison population would be down by 3,000 within 12 months. We would no longer need a new prison.

4) Allow more prisoners to be released after serving half their sentence

Prior to 2002, the Board only saw prisoners serving sentences of more than seven years. Those serving less than seven years were automatically released after serving two-thirds of their sentence. The Parole Act of 2002 increased the role to the Parole Board by defining a ‘long term’ sentence as one of two years or more – thereby making the Board responsible for seeing many more prisoners.

These so-called long term prisoners can only be released before the end of their sentence if the Board concludes they no longer pose an ‘undue risk’ to the community. In recent years it has toughened up to such an extent that the average proportion of their sentence served by long-term inmates has increased from 52% in 2003 to 77% in 2017.

Given that short term prisoners only serve only half their sentence, if we reclassified a greater range of prison sentences as short (say up to five years instead of up to two), that would enable more inmates to be released at the half way mark.

“The average proportion of their sentence served by long-term inmates has increased from 52% in 2003 to 77% in 2017”

Let’s look at the figures. The ‘tough on crime’ legislation passed since 1985 has significantly increased the number of prisoners serving longer and longer sentences (see graph below). Between 1985 and 2015, the number of people given sentences between two and three years went up 475%. In 2017, there were 1,443 inmates in this group. There were 2,694 inmates serving between three and five years.

Graph shows how the number of long term sentences has been rising while the number of  short term sentences has remained largely unchanged

All long-term prisoners have to appear before the Parole Board; they can only be released before the end of their sentence if the Board concludes they no longer pose an ‘undue risk’ to the community. In recent years the Board has toughened up to such an extent that the average proportion of their sentence served by long-term inmates has increased from 52% in 2003 to 77% in 2017.

All long-term prisoners have to appear before the Parole Board; they can only be released before the end of their sentence if the Board concludes they no longer pose an ‘undue risk’ to the community. In recent years the Board has toughened up to such an extent that the average proportion of their sentence served by long-term inmates has increased from 52% in 2003 to 77% in 2017.

So if the government changed the definition of ‘short-term’ to include sentences between two years and three years, that would allow an additional 1,443 inmates to be released after serving half their sentence. If the definition of short term was applied to sentences between two and five years, a total of 2,694 inmates would be released early.

Changing the definition of short term sentence to include prisoners serving between two years and five years would reduce the prison population by about 700.

Instead of serving an average of 77% of their sentence, they would now all serve exactly 50% – a reduction of 27% in sentence length. This means that after five years, there would be 27% less people in prison in the two to five-year cohort. 27% of 2,694 is 727. In other words, changing the definition of short term sentence to include prisoners serving between two years and five years would reduce the prison population by about 700 people.

Add that to the 3,000 removed by the first two strategies described above and the prison population would be down by 3,700.  We would definitely not need a new prison – and the country would save up to $2.5 billion.